The Curious History of the Röntgen Ray

The skeletal hand of a woman, embellished with jewelry and a small spray of flowers, has a distinctly somber and funereal aspect. Nothing in this image connotes living, breathing flesh. Contrast this with the visible interior of a familiar cartoon character standing behind a fluoroscope. Hardly funereal, a cartoon cat is nonetheless neither living nor breathing. But despite Jerry’s intrepid efforts to thwart his nemesis, he’ll never see

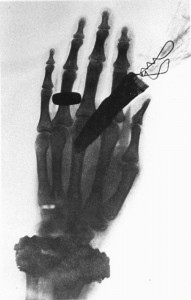

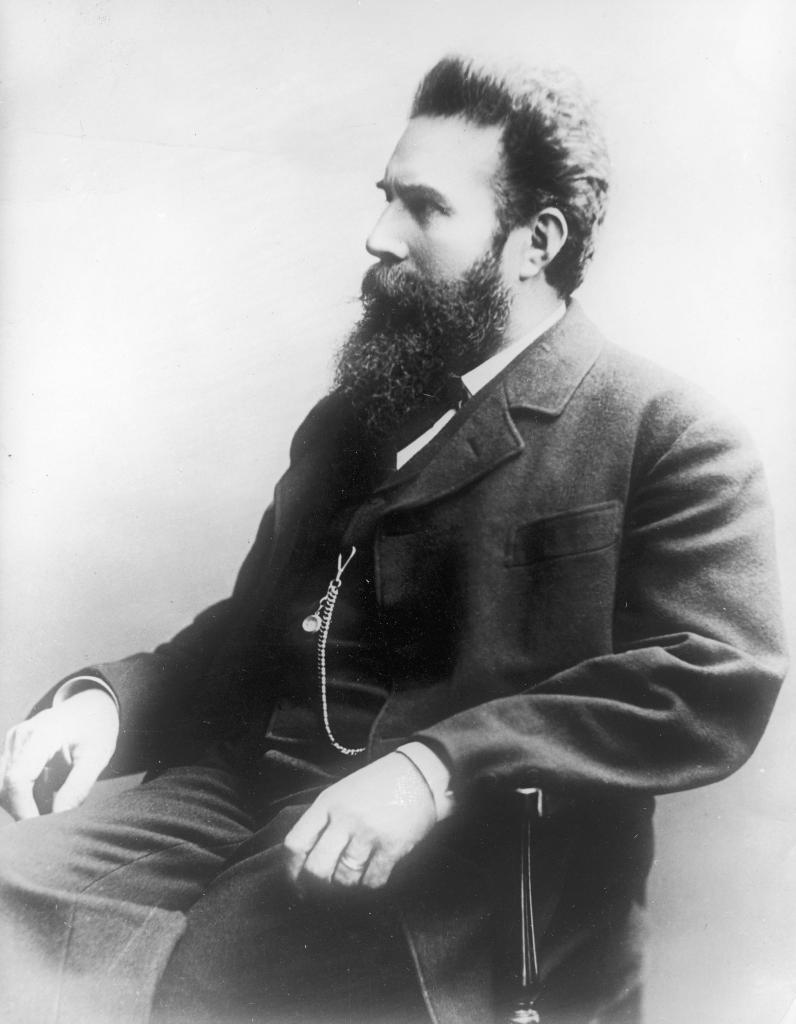

The skeletal hand of a woman, embellished with jewelry and a small spray of flowers, has a distinctly somber and funereal aspect. Nothing in this image connotes living, breathing flesh. Contrast this with the visible interior of a familiar cartoon character standing behind a fluoroscope. Hardly funereal, a cartoon cat is nonetheless neither living nor breathing. But despite Jerry’s intrepid efforts to thwart his nemesis, he’ll never see  Tom’s cold, lifeless, cartoon corpse. The X-ray’s trajectory from a novel, almost magical memento mori to a well-worn trope in popular entertainment is notable for its recurring characters (some of whom, themselves, became somewhat akin to cultural tropes), surprising tangents, dead ends, tragedies, and striking parallels in the arenas of technological progress, visual art, self-help, and general charlatanism. On November 8, 1895, German physics professor Wilhelm Röntgen stumbled on X-rays while experimenting with Crookes tubes – a type of cathode ray tube— in a darkened room. Directing the tube at a screen coated with fluorescent material, he found that, although the tube was wrapped in black paper, the screen lit up; the tube was emitting some kind of light wave. Placing a number of objects between the tube and the screen, he discovered he could see “inside” them. When he subjected his hand to the same treatment, he saw his own bones, darkened within the translucent outlines of skin. Finally, by substituting a photographic plate for the fluorescent screen, he produced the first X-ray photograph using his wife Berthe’s hand as the subject. Upon seeing the result, she allegedly screamed “I have seen my own death!”

Tom’s cold, lifeless, cartoon corpse. The X-ray’s trajectory from a novel, almost magical memento mori to a well-worn trope in popular entertainment is notable for its recurring characters (some of whom, themselves, became somewhat akin to cultural tropes), surprising tangents, dead ends, tragedies, and striking parallels in the arenas of technological progress, visual art, self-help, and general charlatanism. On November 8, 1895, German physics professor Wilhelm Röntgen stumbled on X-rays while experimenting with Crookes tubes – a type of cathode ray tube— in a darkened room. Directing the tube at a screen coated with fluorescent material, he found that, although the tube was wrapped in black paper, the screen lit up; the tube was emitting some kind of light wave. Placing a number of objects between the tube and the screen, he discovered he could see “inside” them. When he subjected his hand to the same treatment, he saw his own bones, darkened within the translucent outlines of skin. Finally, by substituting a photographic plate for the fluorescent screen, he produced the first X-ray photograph using his wife Berthe’s hand as the subject. Upon seeing the result, she allegedly screamed “I have seen my own death!”  Röntgen dubbed his discovery the “X-ray,” for it was an unknown entity. (X-rays are still referred to as Röntgen rays in some countries.) He delivered his paper, “On a new kind of ray,” on December 28, 1895. (Coincidentally, this was also the day the Lumière Bros. held the first public screening of a motion picture for a paying audience.)

Röntgen dubbed his discovery the “X-ray,” for it was an unknown entity. (X-rays are still referred to as Röntgen rays in some countries.) He delivered his paper, “On a new kind of ray,” on December 28, 1895. (Coincidentally, this was also the day the Lumière Bros. held the first public screening of a motion picture for a paying audience.)

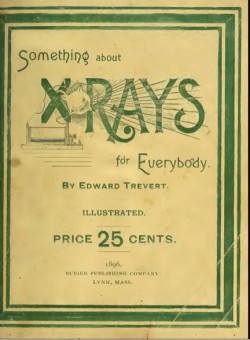

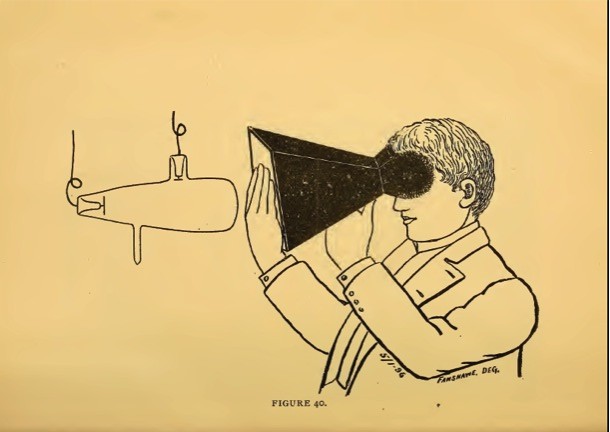

Within a year, the X-ray had thoroughly penetrated the public imagination in Europe and America. The history and continuing impact of X-ray technology in medicine and science is well documented. The history and impact of X-ray technology in popular culture has received far less attention. Aside from its early diagnostic and therapeutic uses (and abuses), the X-ray inspired social commentary and political satire, informed the budding film and photographic arts, materialized in occult practices (and malpractices), peddled everything from condoms to stove polish–in short, became a hot commodity–all because it tapped into the innate, morbid curiosity of the modern psyche. The notion that what had always been inherently invisible and unknown could be revealed to the naked eye by simple scientific means–even by amateurs–was a game-changer. Something About X-rays for Everybody (1896), for example, provided a simple, condensed explanation of the X-ray as well as instructions for the home hobbyist who wished to build his own apparatus:

Its power still misunderstood, this new kind of ray both transformed medical diagnostic technology and invited fanciful speculation about its other “revelatory” capabilities. Despite its overall fascination with the X-ray, in some respects “the general public was not so eager to ‘see through themselves.'” Until this point, the only accurate representations of the body’s interior available were anatomical illustrations and photographs–or the sight of actual corpses and cadavers–all of which were the province of medicine, disease, and death. “On the revolting indecency of seeing people’s bones we need not dwell…Throw the thing into the sea where the fish may contemplate each other’s bones but not for us!” (Cole, p.9). O Roentgen, then the news is true And not a trick or idle rumor That bids us each beware of you And of your grim and graveyard humor. We do not want, like Dr. Swift To take our flesh off and to pose in Our bones, or show each little rift And joint for you to poke your nose in. (Cole, p. 9)

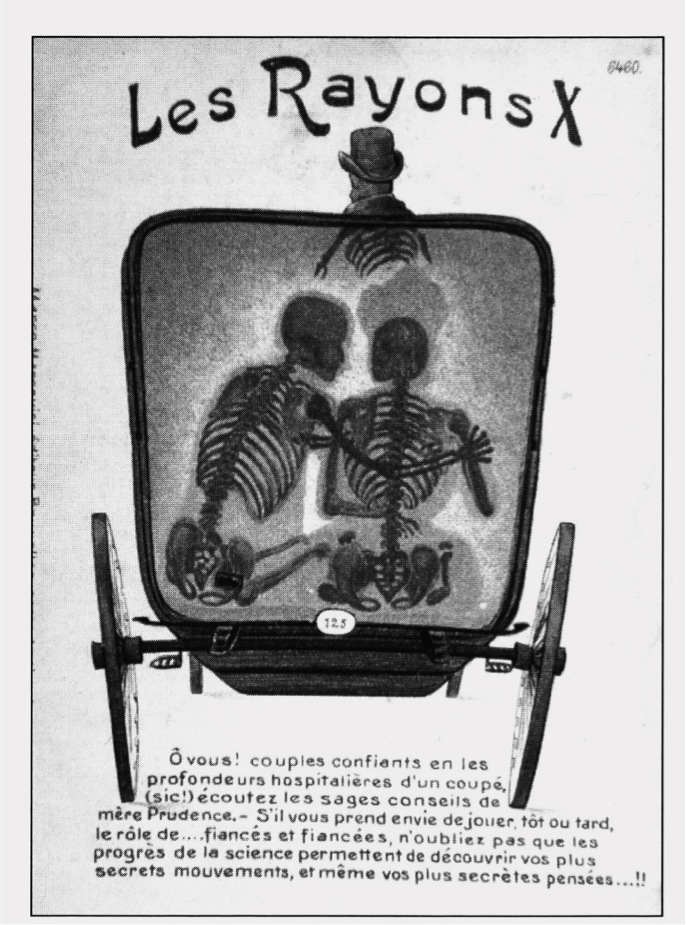

Soon satirists and critics recognized how the qualities of this new kind of ray could enrich social commentary. One of countless examples is this “X-ray of Bryan’s brain” which appeared in the Chicago Daily Times’ October 6, 1896 issue, during the run up to the McKinley-Bryan presidential election (Edwards). Perhaps building on the X-ray’s association with health and medicine—and a growing belief in its salutary effects—this humorous French postcard from the period warns young lovers not to forget that it abolishes any pretense to secrecy, especially when it comes to their clandestine romantic assignations (Pallardy, p. 241). Rakes and virgins beware! However tongue-in-cheek it may be, the card nevertheless plays the physically revelatory power of the X-ray off the day’s social and sexual mores.

A very early British Pathé film, “The X-Rays,” or alternatively, “The X-Ray Fiend” (1897) portrays a similar peril. In this instance, however, the glimpse “inside” the protagonists reveals the man’s less-than-honorable intentions, whereas the virtue of the woman he woos remains unimpeachable, even when irradiated.

The X-Ray Fiend, G.A. Smith (1897). Courtesy BFI.

The X-ray was a remarkable phenomenon, not only for its power and possibility, but for the speed at which it was absorbed into public discourse. Within a year of its discovery, the X-ray had permeated popular culture on several continents. It had seemingly bypassed the nascent information superhighway of the time, which was still a wheel-rutted country road strung with telephone and telegraph wires. It’s as if this invisible light dawned across the globe all at once, illuminating quirks in the public’s imagination, and its anxious anticipation of a new age.

Works Cited

- Elizabeth Cole, Roentgen’s Ray: A Story Of The Discovery Of A Light That Was Never On Land Or Sea. 1935.

- Rebecca Edwards et al., New Spirits: Rethinking the Gilded Age in US History with Rebecca Edwards , retrieved 12/15/13.

- Guy et Marie-José Pallardy, “Cartophilie et radiations: une contribution appréciable àl’histoire de la radiologie.” Histoire des Sciences Médicales. XXXIII: 3, 1999. pp. 231-242.

- Edward Trevert, Something About X-rays for Everybody. Bubier Publishing Company: Lynn, MA, 1896.

Mentions