Although the dangers of X-ray exposure were increasingly understood by clinicians and laypeople, a notable exception to this shift in attitude was shoe-stores’ use of the fluoroscope. From the 1920s through the 1950s these machines were used, presumably, to help salesmen evaluate customers’ feet and better fit them for shoes. In reality, they were novelties used to attract customers. The veneer of science hardly masked the thrill of seeing one’s own insides. The Footoscope, for example, featured two viewers, one for the knowledgeable salesman and one for the curious customer.

Nicola Tesla’s impressive early X-ray of a foot in a boot has nothing on the Footoscope.

Once again, the X-ray was used to sell, and entertain. And as the marketing of entertainment and fun focused more and more on individual experience, the X-ray took on another dimension in popular culture: the novelty. The modern concept of the X-ray was freed from its physics and its machinery. It could simultaneously encompass all it had connoted or represented throughout its development: mystery, scientific progress, danger, revelation, exposure, invasion, health, and death. It became something one could purchase and possess rather than patronize.

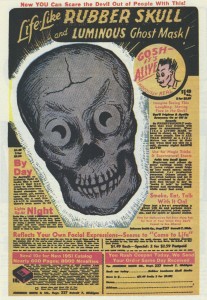

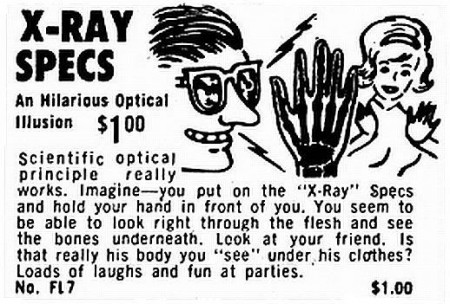

Novelty items like X-Ray Specs invited folks to “surprise your friends with amazing illusory X-ray sight!”, while the memento mori was further reduced to a glow-in-the-dark rubber skull somehow labeled “lifelike.”

Novelty items like X-Ray Specs invited folks to “surprise your friends with amazing illusory X-ray sight!”, while the memento mori was further reduced to a glow-in-the-dark rubber skull somehow labeled “lifelike.”

Fears of transparency first expressed in 1896 have been realized as marketing gimmicks; no one is safe from the prying eyes of a stranger, anywhere.

From page 3 of Acme Novelty Library #10, 1998; reproduced in Print

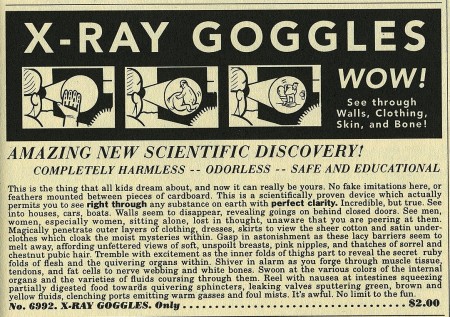

This can’t be any clearer than in the descriptive text of Chris Ware’s spoof ad for X-ray goggles in Acme Novelty Library #10, which plays on tropes of pornographic voyeurism: “See men, women, especially women, sitting alone, lost in thought, unaware that you are peering at them. Magically penetrate outer layers of clothing, dresses, skirts, to view the sheer cotton and satin underclothes which cloak the moist mysteries within…Tremble with excitement as the inner folds of thighs part to reveal the secret ruby folds of flesh and quivering organs…” It merely makes obvious in today’s image-saturated advertising lingo what those more circumspect 1950s ads always suggested. All in all, a far cry from that little ditty in 1896: “We do not want, like Dr. Swift To take our flesh off and to pose in Our bones, or show each little rift And joint for you to poke your nose in.”

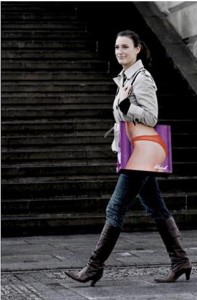

Not much left to the imagination here.

In his review of “X-ray fashion,” Dr. Michael Jackson describes the development of X-ray-proof underwear in the early 20th century, designed to allay fears of patients’ “overexposure.” With the more recent and controversial installation of full-body scanners in airports, fears of prying guards’ eyes resurfaced, and someone saw the profit potential. Travelers wishing to protect their modesty can now purchase X-ray proof underwear (presumably, without lead) in specialty stores or catalogues.

The threat of exposure (and providing entertainment for bored TSA officers) is only skin deep. How would we feel if all they saw were our bones? From Jackson’s essay “X-ray Fashion – A Pictorial Review”

The ironic “promise” of exposure remains a selling point as well, yet in this arena the frisson between public and private has diminished. Accessories, haute couture and off-the-rack apparel play with the idea of public exposure, the key word now being public.

Unlike many folks in 1895, most of us today can at least guess at what our own skeletons look like, without the need to wear a t-shirt or pajamas or a swimsuit printed with the image for reference. Likewise, anyone else can guess at what you look like under your skin too. A pretense to privacy is impossible. As with contemporary portrayals of sexuality, the body, and death (for example) in the public realm, the explicit has supplanted the mysterious. In effect, any contemporary commercial representation of the X-ray thumbs its nose at puritanical attitudes toward the body—in life and death.

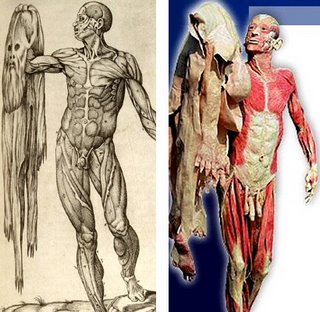

An interesting comparison, from the blog “Spider in the Bathtub“

Early fears of the X-ray’s powers of revelation were founded on the psychological threat it posed to personal privacy: the idea that one’s thoughts and feelings could be revealed and put on public view. But perhaps seeing the image of her own death terrified Berthe Röntgen for a different reason: displaying the most interior part of one’s body creates anonymity. The image of our death takes away our features, our persona, and our individuality.

When placed next to its obvious model, Juan Valverde de Amusco’s 16th century engraving “Anatomia del corpo humano…” , this figure in the contemporary exhibit Body Worlds 3 conveys something quite different. The engraving depicts a man flayed from his public identity–and contemplating it. It’s meant to educate but it’s also a work of art, informed by the tradition of memento mori .The cadaver, a real man, shows us what we all look like (more or less). It’s explicit, not suggestive. Amusco makes me think “Is that all I am?”; Body Worlds 3 reminds me that I’ll never know who this person was.

* * *

Initially, both science and popular culture celebrated both the power and the spectacle of the X-ray: a boon to public health and medical practice, it embodied the potential of scientific research to penetrate unseen worlds of knowledge, and to make it accessible.

But the X-ray revealed so much more. And peering under the surface, we can still see the entwining of commercialism, technology, and popular entertainment; death, desire, and the mass market; satire and deception; morbidity, aesthetics, and fear. Whether this indicates something pathological or is merely the normal evolution of modern invention, the proper domain of X-ray vision is sure to remain a bone of contention.

Works Consulted:

- Berko, Lex. “A Visual Consideration of How We Relate to Death.” Motherboard. Retreived 7/2/14.

- Jackson, Dr. Michael. “X-Ray Fashion: A Pictorial Review.” International Society for the History of Radiology, retrieved 2/27/2013.

- Sedelmaier, J.J. “Amazing X-Ray Glasses and 9000 Other Novelties: Johnson Smith & Co.” Print. Retrieved 2/27/13.

- U.S. National Library of Medicine, 18 September 2002, “Dream Anatomy: Anatomical Dreamtime.” Retrieved 7/2/2014.

2 thoughts on “The Curious History of the Röntgen Ray, Part VI: Completely Harmless — Odorless — Safe and Educational”