The Technology of Popular Entertainment

The X-ray fast became the product that every modern physician should possess. When physicians did not have their own equipment, patients needing interior imaging or radiation treatment could visit X-ray “salons”; although these differed little from a modern radiology offices, they presented themselves more like photography studios than medical establishments.

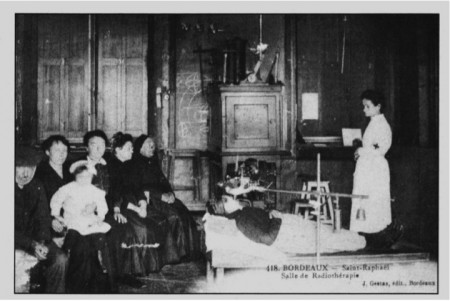

The X-ray fast became the product that every modern physician should possess. When physicians did not have their own equipment, patients needing interior imaging or radiation treatment could visit X-ray “salons”; although these differed little from a modern radiology offices, they presented themselves more like photography studios than medical establishments.

A French postcard depicts the waiting room of an X-ray salon

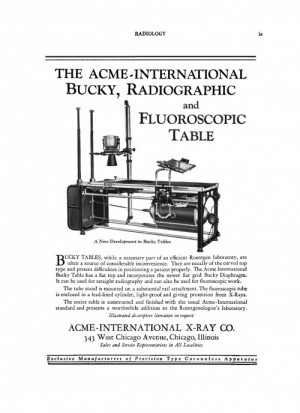

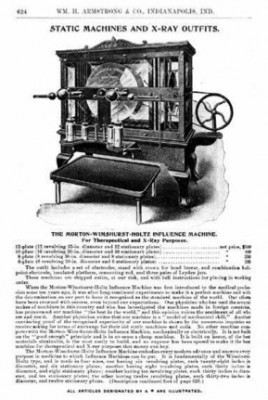

Early professional X-ray apparatus, used for imaging and radiotherapy, could take up most of a room; the Crookes tubes required the power of loud generators, which burned fuel. These machines were rapidly improved upon, Soon equipment was manufactured and marketed to radiologists and physicians with an emphasis on visual appeal, designed to impress patients and colleagues. For patients, being X-rayed—whether for diagnostic or therapeutic purposes—could verge on aesthetic experience.

The X-ray was part of general “domestication” of physics at work in the latter third of the 19th century, through inventions including the telephone, recorded sound and playback, personal cameras, and motion pictures. As growing technological knowledge was applied to everyday interests and activities, even middle-class consumers could become involved in the process of invention. It was this popular physics that helped make film, sound, photography, telephony—and now X-rays—both attractive and available to the layperson for fun and profit, as a book like Something About X-rays for Everybody makes clear.

The Lumiere Brothers, pioneering the new film technology on the Continent, had coincidentally screened a film for the first time the very day Röntgen’s paper was published. As a new form of photography, the X-ray naturally interested them, for it suggested that image-making might be possible through as-yet undiscovered methods. Auguste Lumiere was especially intrigued, and was the first person in France to create and use a working X-ray machine.

Edison and his fluoroscope

It should be no surprise that Thomas Edison, who had just given the world motion pictures and the Kinetoscope, as well as new developments in electric lighting, also became heavily involved with the progress of X-ray technology at this time. It offered exciting opportunities to explore the electromagnetic spectrum. (Edison’s scientific nemesis, Nicola Tesla, also experimented quite successfully with X-rays, but more about him later.)

While photography, film, and recorded sound became thoroughly domesticated, the X-ray never lost its specialized, scientific aura for the general public; for those who were not home enthusiasts or at least technologically-literate, its capabilities could be at once empirically infallible and, ironically, mysterious and uncanny. The X-ray offered the competing appeal of both fantasy and fact.

In an era when hemlines below the ankles still ensured a polite woman’s modesty, the threat and promise of exposure offered harmless titillation and excitement. The body, private thoughts, and one’s “true nature”–was anything safe from prying rays? The self was now an object (and subject) of entertainment. This, and the relatively straightforward technology that made simple X-ray set-ups easy to create and somewhat portable, had predictable results. What do you get when you combine a desire for mildly illicit thrills with affordability and ubiquity? Popular entertainment and cheap novelties.

This, and the relatively straightforward technology that made simple X-ray set-ups easy to create and somewhat portable, had predictable results. What do you get when you combine a desire for mildly illicit thrills with affordability and ubiquity? Popular entertainment and cheap novelties.

World’s Fairs specialized in introducing modern technology to the general public, sometimes–as with fax machines–so modern it wouldn’t become available to consumers for decades. These showcases demonstrated the high entertainment value of technology: as we were all told as youngsters, learning can be fun. In May 1896, Thomas Edison and his assistant Clarence Dally went to the National Electric Light Association exhibition in New York City to demonstrate their fluoroscope. Hundreds of people lined up to stand before a fluorescent screen and peer into the scope to see their own bones. The 1899 Omaha Trans-Mississippi Exposition featured a Röntgen Ray booth,  and while the 1901 Pan-American Fair in Buffalo, NY may be best remembered as the site of President William McKinley’s assassination, an X-ray machine, in which fair-goers could see their skeletons, was among the most popular exhibits. * X-rays once again made their appearance at the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair, and would continue to serve as public attractions well into the 20th century.

and while the 1901 Pan-American Fair in Buffalo, NY may be best remembered as the site of President William McKinley’s assassination, an X-ray machine, in which fair-goers could see their skeletons, was among the most popular exhibits. * X-rays once again made their appearance at the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair, and would continue to serve as public attractions well into the 20th century.

Within two years of the X-ray’s first scientific demonstrations, X-ray booths were popping up at expositions, fairs, and other arenas of public amusement. X-ray “hand portraits” were in vogue. A precursor to the one-day-ubiquitous public photo booth, these attractions made one’s unique, internal characteristics visible and accessible. In this way, they also had much in common with modern cartoon caricatures (also ubiquitous), which exaggerate unique physical characteristics and facial expressions to better capture (or reveal) the sitter’s personality.

This domestication of X-ray technology as popular entertainment signified an increasing comfort with the means of exposing a person’s deepest, otherwise inaccessible self in the most literal sense. On a psychological level this concept of self—the unconscious—would not gain acceptance for nearly a decade. It took eight years for Sigmund Freud’s Interpretation of Dreams, first published in 1900, to sell out its initial print run of 600 copies.

* The Hall of Man pavilion at the 1939 World’s Fair in New York featured a new “stand-up” X-ray booth that utilized a rapid imaging technology at a low cost. Capitalizing on the likely appeal of this new development for X-ray-curious fair-goers, a medical commission arranged for and strongly encouraged visitors to undergo X-rays. This was a public health effort, offering individual screening for tuberculosis and heart disease and a broad survey of the public for hidden disease—an important factor to the success of a nationwide tuberculosis control program.

Works Consulted:

- Robert C. Kennedy,On this Day: June 8, 1901.” Retrieved April 18, 2014.

- Gilbert King, “Clarence Dally – the Man who gave Edison X-ray vision.” Retrieved April 18, 2014.

- Hugh O’Connor, “Science at the Fair.” New York Times. May 28, 1939. Retrieved April 18, 2014.

- Guy et Marie-José Pallardy, “Cartophilie et radiations: une contribution appréciable àl’histoire de la radiologie.”Histoire des Sciences Médicales. XXXIII: 3, 1999. pp. 231-242.

- Expomuseum, Pan-American Exposition. Retrieved April 18, 2014.

- “X-rays, ‘fax machines’ and ice cream cones debut at 1904 World’s Fair.” Newsroom, Washington University in St. Louis. Retrieved April 18, 2014.